Poor ol’ Jimmy sits alone in the moonlight

He saw his woman kiss another man

So he takes a ladder, steals the stars from the sky

Puts on Sinatra and starts to cry…

– Stephen Bishop, “On and On,” 1977

There it was, another brief item buried in the Google News feed connected to Frank Sinatra’s centennial year in 2015. The opening sentence instantaneously garnered my attention: “The first pop music concept album ever released, Frank Sinatra’s In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning is celebrating its 60th birthday this week.”

In a time when the world continued to reexamine the significance of Frank Sinatra, this was but an infinitesimal, blip-on-the-screen item when it was published that December. And yet, the aftershocks of a disc that was recorded back in 1955 are still being felt all these years later.

A three-in-the-morning rumination on misery, In The Wee Small Hours of the Morning, captured Sinatra’s emotional nose-dive after he and second wife Ava Gardner’s marriage began to crumble to dust. Despite its prevailing gloom, the disc’s influence became so widespread that it is now credited with setting the standard for all concept albums thereafter.

Previously, Sinatra had made a name for himself by generating flashy, big-band-backed records beginning in 1939. In real life, however, the winds never blew in one direction for Frank Sinatra. They inevitably swirled. ”Being an 18-karat manic-depressive, and having lived a life of violent emotional contradictions,” Sinatra once admitted. “I have an over-acute capacity for sadness as well as elation. Whatever else has been said about me is unimportant. When I sing, I believe, I’m honest.’” Ultimately, In The Wee Small Hours of The Morning was nothing less than a 52-minute hymn to pathos.

Consequently, it made perfect sense that the mercurial Sinatra followed such a depressing album a year later with the ultimate buzz: his 1956 hyperkinetic release, Songs for Swingin Lovers, which featured such beloved chestnuts as “I’ve Got You Under My Skin,” “Old Devil Moon,” and “You Make Me Feel So Young.” As Bruce Springsteen said years later, “When I need a pick-me-up, my default has long been putting on Songs for Swinging Lovers.”

Thus, when Frank then came out with another “downer” concept record 19 months later, critics and fans alike braced themselves for one of Frank’s emotionally harrowing, roller-coaster rides. But Frank Sinatra Sings For Only the Lonely wasn’t merely a 1958 follow-up to In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning.

It turned out to be his masterpiece.

More than two decades after his death, the widespread appreciation for Sinatra as an artistic immortal has reached universal affirmation. When historians list Frank Sinatra’s assorted “firsts,” his place on America’s musical Mount Rushmore is now rock-solid. After all, he was the first pop superstar of the modern era. He possessed the most recognizable singing voice in the world. He was the most significant male vocalist to bridge jazz to the wider pool of mainstream music. His incomparable “phrasing” set the standard for musicians of all stripes. He publicized such future leviathans as Billie Holiday, Count Basie, and Nina Simone when they were struggling to be heard. Because of his association with the fledgling Capitol Records, Sinatra, along with Nat Cole, moved the epicenter of the American recording industry from New York to Southern California. He was the founding father of Reprise Records, a company “created by artists for artists,” something the Beatles tried to replicate years later with Apple Records. Finally, it was Frank Sinatra who was the originator of what would become known as “the concept album.”

Of course, a “concept album is a studio record where all musical or lyrical ideas contribute to a single overall theme or unified story.” Those of us who grew up in the 1960s could easily rattle off a seedbed of concept albums that are now considered classic rock’s “must-have” discs. A short-list might include Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon; the Moody Blues’ In Search of the Lost Chord; David Bowie’s The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust; Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going’ On, and The Who’s Tommy.

Casual rock fans believe that the idea of the concept album surfaced somewhere around the time of the Beatles’ Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. In actuality, it was Sinatra who turned out to be the consigliere of the genre when he introduced the notion a dozen years earlier with In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning. Whereas that 1955 recording was certainly extraordinary, it is the brutal honesty, utter despair, and lingering regret of 1958’s Frank Sinatra Sings for Only the Lonely that hangs like a shroud over every other concept album released since then. Only Joni Mitchell’s Blue and Bob Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks come close to it.

In the end, creating the very idea of a concept album was no reach for someone like Sinatra, who had famously sung for both the Harry James and Tommy Dorsey-led bands at the outset of his career. Sinatra came up with the novel idea through the process of osmosis. After all, his work as a frontman in the 1940s with both Harry James and Tommy Dorsey gave him an education in the musical bookends of sequence and connotation. When he started traveling around the country as part of a big band, Sinatra learned that there had to be a connection between the orchestra and its audience. As he became a seasoned “front-man,” he learned that thematic scheming was an essential part of any successful musical “package.”

This idea eventually led him to become increasingly obsessed with the order of his songs that comprised his old 78 RPM albums as a Columbia artist in the forties. (As an aside, Sinatra has long been credited with being the first recording artist to come up with the idea of interchanging “fast songs” and slow ballads in order to sustain the attention of the listener. It did not hurt that Sinatra, riddled with OCD throughout his life, began to look to his songs through the lens of order).

When the industry came out with the 33 RPM long-playing album in the mid-1950s, Sinatra had become even more obsessed with the process.

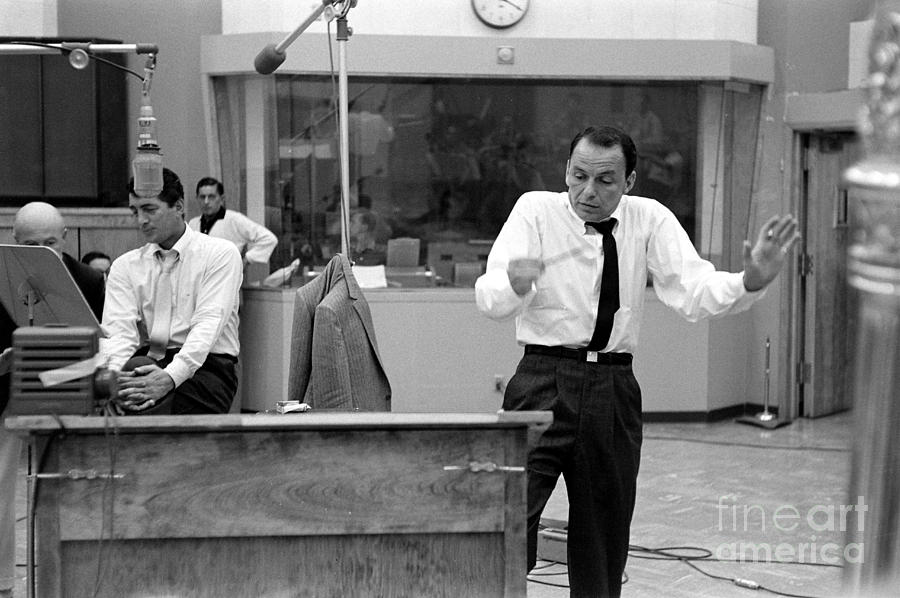

From his perspective, the songs had to make sense in terms of arrangement, theme, and sound. Thus, when Ava Gardner officially divorced him in 1957, he knew that he had to produce an album capturing “the blues” he felt at the time. The genesis of Frank Sinatra Sings For Only the Lonely, then, is largely biographical. Consequently, in May 1958, Sinatra, renowned arranger and producer Nelson Riddle, and conductor Felix Slatkin entered the famed Capitol Studios at 1750 Vine in Hollywood to record the follow-up to In Wee Small Hours of the Morning.

While Sinatra and Riddle had already reinvented contemporary music by creating a sound that was inimitable, their customary big band sound would not be the musical centerpiece for this particular record. At Sinatra’s request, classical maestro Felix Slatkin, a significant talent as well, brought with him a gaggle of orchestral musicians with him to the studio. As he had done years earlier with his first celebrated producer at Columbia, Alex Stordahl, Frank would be the main instrument backed by a minimalist orchestra that would play off the singer’s voice. Over the next eleven days, the collected ensemble repeatedly heard two phrases directed at them from Sinatra himself: follow me and less is more. In recalling the celebrated sessions that encompassed Only the Lonely, jazz guitarist Al Viola recalled, “Classical musicians don’t normally riff, but for Sinatra, they did, and it worked. They played off each other like it was the most natural thing in the world for them to do.”

In a canon of 12 torch songs that comprise Frank Sinatra Sings For Only the Lonely, an astonishing eight undisputed masterworks provide the crux for the album. The title track, written by Rat Pack pals Sammy Cahn and Jimmy Van Heusen, serves as the quintessential splash-in-the-face that promptly triggers emotive anguish. Even at a casual listen, it is the fidelity one hears that makes this opening salvo so powerful. Part of that comes from Sinatra’s peerless facility for phrasing – his ability to seamlessly articulate each word and expression.

As the late Pete Hamill once famously pointed out, it was Frank Sinatra’s exquisite phrasing that taught more people how to speak English as a second language than any other person in human history. Even more remarkably, Sinatra’s aptitude to insert distinctive musical punches into each syllable separates him from everyone else. Finally, the tonal quality of his singing is unmatched. His voice sounds as clear as a bell on every word and phrase he sings.

But as any vocalist knows, phrasing is more than just pronunciation. It also contains another potent vocal element – breath control. Sinatra, like nearly every other great jazz and pop musician of his time, learned that indispensable element from the great Louis Armstrong. In addition, there is the lilt, the playfulness, the dragging out of words to bring the meaning powerfully to life. Veteran songwriter Sammy Cahn once observed, “When Frank sings ‘lovely,’ he makes it sound love-e-ly as in ‘Weather-wise it’s such a love-e-ly day’ in ‘Come Fly with Me.’ Likewise, when he sings ‘Lonely” as in ‘Only the Lonely,’ he makes it such a lonely word.”

The second ballad on the album, “Angel Eyes,” is so fastidiously arranged by Nelson Riddle that Sinatra’s voice serves primarily as the lead instrument here. Because both arranger/producer and singer were notable collaborators, teamwork lay at the heart of their musicianship. As Sinatra and Riddle inevitably seemed to do whenever they worked together, their considerable egos were pushed aside, and “the song became the thing.” Thus, “Angel Eyes” is nothing less than a three-minute narrative that tells a profoundly heartrending tale. “Sinatra’s ability to tell a story had consistently gotten sharper as the voice grew deeper and the textures surrounding it richer,” claims musicologist Will Friedwald. Riddle made damned sure that he gave the vocalist room to maneuver throughout the song. Sinatra then played off the instrumentation faultlessly. Finally, there was this: When Frank was a young pop star in the ’40s with a vibrant tenor, his voice was the equivalent of a new spring day. On “Angel Eyes, Sinatra, now 43-years old, sounds like finely crafted wine whose “chops” have been fermenting in a keg for years. He is not some young pup who is aching; Sinatra’s been around the block more than a few times, so the heartbreak here is even more palpable.

Bob Haggart’s and Johnny Burke’s beloved American Songbook classic, “What’s New” is given an entirely new interpretation by Sinatra in the album’s fabled third song. Previously, the standard had been interpreted by scores of singers in a condescendingly melodramatic way. The effect was comparable to leaving a cake in the oven 10-minutes too long. In contrast, Sinatra’s version is both understated and coy, making it even more wrenching. Linda Ronstadt, who recorded “What’s New” with Nelson Riddle 25-years later, said that she “tiptoed” around ballad at first before agreeing to record it. She freely admitted to Larry King in a celebrated 2003 interview, “How can you top Sinatra?” The orchestration as charted by Riddle is evocatively restrained. To add to the gloom, trombonist Ray Sims plays off Sinatra’s voice like a mournful wail in pea-soup fog. It is one of those numbers that stays with you well after the song is over.

“Willow, Weep for Me,” the record’s fifth number, is composer Ann Ronell’s heartbreaking, cause-and-effect breakup song – the musical equivalent of the aftereffects of a major nor’easter. It is no accident that Frank, who long revered Billie Holiday, wanted to record one of her more acclaimed ballads. Six months before he released Frank Sinatra Sings For Only the Lonely, Sinatra stated famously that…“’Lady Day is unquestionably the most important influence on American popular music in the last 20 years. With a few exceptions, every major pop singer in the United States during her generation has been touched in some way by her genius.” Ultimately, Sinatra not only gives a nod to Holiday in “Willow, Weep for Me,” but he ends the tune with the enduring plea: “Murmur to the night/Hide its starry light/So none will find me sighing/Crying all alone/Weeping willow tree/Weep in sympathy/Bend your branches down along the ground – and cover me/Listen to me plea/Hear me willow – and weep for me.”

Of course, when Frank recorded the number, “The First Lady of Jazz” would have only a year to live. In 1959, Holiday died of cirrhosis of the liver at 44 in her bed at New York City’s Metropolitan Hospital under house arrest, poverty-stricken and despondent. It was Sinatra who not only paid off all of her debts but then ended up funding Holiday’s entire service – the largest, most celebrated funeral in the city that year. In “Willow, Weep for Me” Sinatra’s haunting voice throughout the dirge is nothing less than a poignant foreshadow of Billie Holiday’s impending demise.

“Blues in the Night,” the classic pop standard composed in 1941 by the celebrated songwriting team of Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer, proves to be a solitary inhale in an album ladened with exhales. The seventh ballad in the album, this extraordinary version should be Exhibit A as to why experts such as Wynton Marsalis have long claimed that Sinatra is “a jazz singer in all respects.” Recorded on June 24, 1958, there is no counterfeit swooning in Frank’s version of “Blues in the Night.” Instead, his voice sweeps; dips; soars, and propels like a turbulent ocean. As Billy Joel once stated, “Sinatra’s voice expresses more eloquence than I can ever say in mere words.” Years ago, when I played the ballad for a fellow musical pal, he sighed: “Frank sings ‘Blues in the Night’ so persuasively that it makes me want to ditch my girlfriend, go to a bar, and cry into my beer.”

“Guess I’ll Hang My Tears Out to Dry,” the album’s most searing tune and the ninth song on the record has eventually become one of Sinatra’s most enduring numbers. While he was known as “One-take Frank” in the movie business, his fastidiousness when making music was legendary. “Guess I’ll Hang My Tears Out to Dry” took almost a day of precise outtakes to get it right, according to chronicler Will Friedwald. As he did on all 12 tracks on Only the Lonely, Sinatra would inevitably enter the studio; greet the musicians individually; saunter up to the front of the room; make notations on the sheet, and then patiently walk through what he wanted to hear from each musician. “Every time you saw him enter the studio to record, it became a workshop into how to make a textbook record,” Quincy Jones said near the end of Sinatra’s career. There are mythical bootlegs of Sinatra’s precise directions to his supporting musicians in scores of sessions out on YouTube. Like an experienced traffic controller, you hear him patiently walking his band through a maze of notes that eventually evolves into a highly imaginative, intuitive sound. When I first heard such outtakes, thanks to New York radio personality Jonathan Schwartz, it reminded me of Leonard Bernstein’s sagacious entries that framed his epic Young People’s Concerts Series back in the sixties.

In “Guess I’ll Hang My Teardrops Out to Dry,” the orchestra and the singer create asymmetry that is indistinguishable, two forces of nature that have merged seamlessly. As with every ballad on this album, the storyline means everything here. Sinatra is a storyteller here weaving out a story that grips your heart and hurls it into the abyss. It all leads to a Casablanca-like ending: “’Yes’ – somebody said/ ‘Just forget about her’/So I gave that treatment a try/And strangely enough/I got along without her/Then one day/She passed me right by/Oh, well…..” When the tune ends, you feel as if the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock has just gone out for the last time.

“Spring is Here,” the record’s 10th song, is an old Richard Rodgers/Lorenz Hart standard that had long bordered on schmaltz until Sinatra reinvented the song in a tour de force rendering. Previous to Frank’s version, it was considered a novelty tune without much substance to it. When such accomplished singers such as Jo Stafford, Bing Crosby, and Billy Eckstine sang it prior to Sinatra, their individual versions sounded slightly repentant; all three artists seem reluctant to even sink even their toes into its misery. Not Sinatra. He grabs a hold of the song at the first note, plunges in headfirst, and then plummets to the muck at the very bottom. In so doing, he claims it as his own and produces an authentic classic in the process. Of course, it is that personal touch that separates Sinatra from nearly every other artist. As songwriter Frank Military once declared, “When you listen to Frank, you always believe that he is singing directly to you.”

I can personally vouch for this for when I saw Sinatra perform live at the Jacksonville Coliseum back in 1976. I swore he was belting out number after number to me alone in a coliseum full of people. No wonder that one of his longstanding staples was entitled, “This Song’s For You.”

The concluding ballad of the album, “One for My Baby (And One More for the Road)” is, for most Sinatraologists, the greatest thing he ever recorded. An over-the-top purist, Frank felt that the Arlen/Mercer standard was written especially for him and that only he could do any justice to it. Because of his rank perfectionism, Sinatra ended up recording the ultimate male torch song an astounding six times in four different decades. Nearly everyone agrees, however, that the version he inserted to conclude Frank Sinatra Sings For Only the Lonely was his best. Miles Davis always claimed that Sinatra “…sounded fundamentally soulful on that number, which is why nobody has ever touched it.” Ella Fitzgerald used to perform regularly “One for My Baby” to live audiences, invariably referring to it as “Frank’s song.” Out of sheer respect, Tony Bennett refused to record it for more than 35 years until he finally gave in and included it as part of his 1993 tribute album to Sinatra, Perfectly Frank.

So what makes “One for My Baby (And One More for the Road”) so magical? For most fans, it is the forlornness in Sinatra’s voice; the intentional hesitation in his phrasing; the crushing refrain; the heartbeat-like, call-response provided by longtime Sinatra pianist Bill Miller, and the pillowed strings that are flawlessly layered to precision by Nelson Riddle and Felix Slatkin. All of these elements fuse into one, creating a genuine chef-d’oeuvre. People living centuries from now will continue to listen to this song in wonder. In my mind, it is the perfect ending to a perfect album.

Although the record ultimately made it to number one on the Billboard album chart in October 1958, Frank Sinatra Sings For Only the Lonely was subsequently awarded just one Grammy the following winter. Inexplicably, it was for the disc’s perplexing cover, an original painting of Sinatra by Nick Volpe, depicting a morose Frank as a Pagliacci-like wag. To correct the obvious faux pas, the Grammy powers-that-be inducted Only the Lonely into their Hall of Fame a year after Sinatra’s death in 1999. By then, Time Magazine had already named it one of the Top 100 musical albums of the century. That same year, critic Jim Emerson wrote, “The bleakest and blackest album of popular songs ever recorded in a hundred years, so quietly powerful it can leave you slumped in your chair with the ice cubes still rattling in your glass. Every single “suicide song” (as Sinatra liked to call ’em) on Only the Lonely is a stunner that will take your breath away.” A few years later, Amy Winehouse called the record, “The single greatest album ever recorded, period.”

And, so, more than six decades after the release of Frank Sinatra Sings For Only the Lonely, the hurt still burns; the regrets still linger, the music remains set in the present tense. The singer seems to be at the point of death in each and every number, and yet there is no other album out there in which you feel more alive after listening to it.

I guess that was Sinatra’s point all along.

I am a fan of the great only the lonely Frank Sinatra since way back to his voice by 45 or in tapes years later by c, d, now on D, v, d,, the one that I treasure the most is The Sinatra Trilogy, a very inspiring kind of c, d, way back25 years ago, how I wish I have one for the last time,,

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very good article with one egregious error. Sinatra never sang a song called “This Song’s For You.” He sang (and recorded four times) Jerome Kern’s “The Song Is You.”

LikeLiked by 1 person