Every great work of art has two faces – one that is timely and that represents its own era and one that is timeless and looks beyond the present to something approaching eternity.

While the Beatles’ 1967 release, Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, is a magnum opus of both time and moment, these days, it seems dated and disconnected. On the other hand, Rubber Soul, recorded 19 months previously, sounds both contemporary and enduring.

Of course, there are a few albums that contain the bookends of both timelessness and immortality: Sinatra’s Only the Lonely; Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue; Dave Brubeck’s Take Five; Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks; Carole King’s Tapestry; Joni Mitchell’s Blue – to name a few. While these frontliners were seasoned artists by the time their singular masterpieces were released, Van Morrison was just 22 years old when he recorded 1968’s Astral Weeks. According to a recent survey in Rolling Stone, Morrison’s “modest little jazz-rock album” remains the favorite for more than two-thirds of all of the reviewers of the magazine. There’s Astral Weeks, and then there’s every other album.

So how can an album that waxes poetic about people stunned by life, completely overwhelmed, stalled in their skins, paralyzed by the enormity of what in one moment of vision they can somehow grasp remain so beloved? Those of us who have been enchanted by it would say that the recording is a perfect storm of provocative lyrics, inspired musicianship, and incomparable vocals.

Like some supernatural warlock, the youthful Morrison sounds as if he had lived several lives simultaneously. Irish to the core, filled with remorse that time has somehow passed him by even as he attempts to take in everything that came his way, Van sings here the way his fellow countryman, John Keats, once wrote – unfettered and resolute.

“I once saw a film on the life of John McCormack, the great Irish tenor,” Morrison stated to Rolling Stone’s Ralph Gleason three years after the release of Astral Weeks. “In the film, McCormick played himself. During one portion of the film, McCormack explains to his accompanist that the elements necessary to mark the important voice off from the other good ones were very specific. ‘You have to have,’ he said, ‘the yarrrragh in your voice.’” After just one listening to Astral Weeks, it is evident that Van Morrison has the yarrrragh.

Recorded some 14 months after his highly-praised solo debut album, Blowin’ Your Mind, was released (which was highlighted by his timeless anthem, “Brown-eyed Girl”), Morrison’s follow-up 53-minute album was recorded in October 1968 amidst some profound personal tumult. In retrospect, Van had been sued, threatened with deportation, and then harassed by his old company, Bang Records throughout much of that tumultuous year. This led him to sign on with a more prestigious label, Warner Brothers, who finally secured him the legal protection that Morrison ultimately needed. Thus, Bang Records had wanted Van to write unswerving pop hits in the vein of his previous works, “Friday’s Child” and “The Midnight Special.”

“I was unwilling to be looked at as a musical hit factory. I wanted to dabble without some record executive telling me what my musical tastes should be,” Morrison said in a lengthy interview with Crawdaddy’s Lester Bangs a few years later.

By the middle of 1968, Van was living in Cambridge, Massachusetts with his new American wife, Janet “Planet” Rigsbee. Morrison, a native of East Belfast, Northern Ireland, had made a name for himself in the British Isles as the lead singer of the mid-sixties pop-soul group, Them, a quartet who had scored two seminal hits written by Van, “Gloria,” and “Here Comes the Night.”

Morrison finally ventured to the States to make it as a soloist in early ’67, but by the time Astral Weeks was recorded, he had already become wizened to the unsavory ways of the American recording business. In retrospect, he was not looking for money but complete artistic control. “Money was secondary. My music was everything,” Van admitted later on to Rolling Stone’s Ralph Gleason.

While he was getting sued by Bang Records, Morrison had begun to explore the depths of musical improvisation with an eclectic assortment of students from Boston’s acclaimed Berklee School of Music. By the summer of ’68, he had begun playing local jazz clubs in both Boston and Cambridge, where, he said, “I could feel the freedom of music that I was not feeling in my professional life that had then been put on hold.” He had authored an assortment of disparate songs by then, many of them based on his Belfast youth. When Van finally was released from his suffocating Bang, Inc., contract, he informed Warner Brothers’ executives in September that he wanted to make a very different record at the label’s studio in Midtown Manhattan. Thankfully, the powers-that-be at Warner Brothers acquiesced.

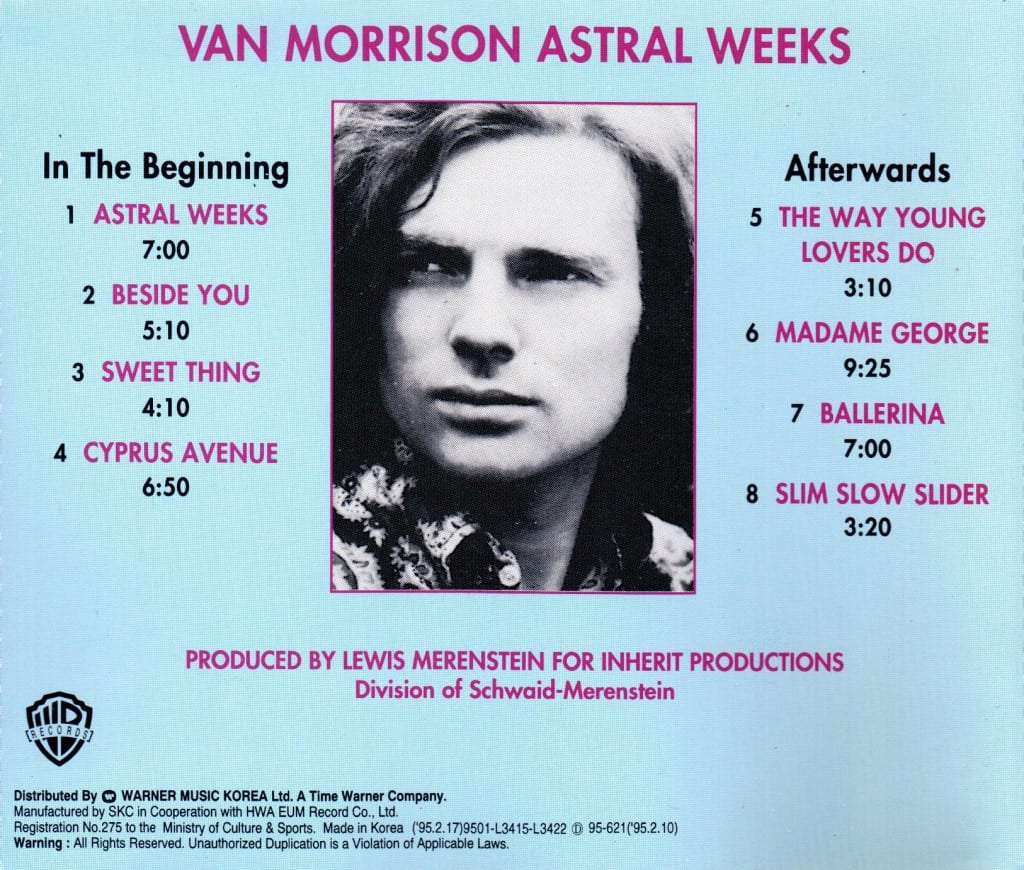

Employing a heady combination of his own intuition and some word-of-mouth advice from his Berklee-Boston comrades, Morrison then hired veteran jazz producer Lewis Merenstein to produce the record and insisted that stand-up bassist Richard Davis serve as the rhythmic underpinning for all eight of Astral Weeks’ musical compositions. Guitarist Jay Berliner, drummer Connie Kay, and percussionist and string arranger Warren Smith, Jr., formed the rest of the impromptu band behind Morrison’s soaring vocals and expressive acoustic guitar accompaniment.

“We recorded the album in three sessions over a two-week period,” Morrison recalled to Dave Marsh in a 1998 Rolling Stone interview. “I kept changing my songs lyrically. We would then gather the band together, and play it on my acoustic as I sang. It never took more than a few listens for them to get them to work and record what I had outlined. It was the ultimate riffing.”

Incredibly, Astral Weeks turned out to be neither rock nor folk nor jazz nor blues, though there are traces of all four in the music and in Morrison’s voice which sounds like a bugle call for the capriciousness of life. Despite the fact that many have classified it as a jazz album, there are virtually no musical solos that would dominate his much more celebrated follow-up, Moondance. While there are interludes of breathtaking symmetry when the music surges and repels, rises and falls, around Van’s lilting voice, the classification of Astral Weeks has always been up for grabs.

After the disc was released on November 29, 1968, Morrison admitted then that he preferred playing small clubs because of the intimacy of such venues and when asked about all the patrons clinking their glasses, intruding on his performances, he whimsically stated, “You put your drink down when you really get into it.”

Of course, Astral Weeks better showcases those powers of observation. Van sees all the little things, even though the big things often get in the way. He provides details that may seem mundane on the surface, such as throwing pennies off a bridge in his graphic ballad, “Madame George.” Nevertheless, the simple act of penny-throwing becomes a metaphor for something much grander. Basically, it’s about adolescence – most of the album is – but more specifically, teenaged idling and carelessness — you know, when one could get away with wasting precious minutes with such a mindless activity and at the same time, not really be concerned with the consequences. The entire exercise is intimate. This is no stadium-induced album but a private conversation between friends. Van’s lyrics sound like a Charlie Parker alto sax solo – unrestrained syncopation and totally unencumbered. In the final analysis, there is an impressionistic-painting-element to the entire affair – a musical pointillism.

“All the scrapbooks built together stuck with glue

And I’ll stand beside you, beside you

Oh child, to never wonder why

To never, never, never, never wonder why at all

To never, never, never, never wonder why

It’s gotta be, it has to be – you “

The album begins with the title track, “Astral Weeks,” and the searing lines: “If I ventured in the slipstream/between the viaducts of your dream/where immobile steel rims crack/and the ditch in the back roads stop,” verses that rival Bob Dylan and Joni Mitchell for unadulterated imagery and context. There is a lilting impetuousness to the tune; it somehow sounds fresh every time you hear it played. The playful back-and-forth between Morrison’s little ensemble captures the tone of the lyrics which are decidedly stream-of-consciousness.

The disc’s second number, “Beside You,” commences with an unforgettable exchange between guitarist Jay Berliner and Van’s potent vocals that seem to wrap themselves around one another. In addition, the haunting tenor of the ballad is as permeating as a relentless summer thunderstorm. While many have described it as a love ballad, there is a spirituality present that would become evident in scores of Morrison songs later on. Yes, we inevitably travel the world as sole adventurers, but to make sense of it, it’s always better to spring forth with someone you love.

The third tune, “Sweet Thing,” the only number on Astral Weeks to receive airplay as a single, remains one of Van’s most requested concert songs. Over an endlessly descending, circular progression, Morrison sings hopeful lyrics about nature and a romantic partner, with a hint of regret sprinkled in: ‘And I will stroll the merry way.’ The band continues to cook throughout this most infectious release, especially in its lilting bridge sections when the band doesn’t just complement the singer; the instrumentalists become interchangeable with Morrison’s evocative vocals. Like all of the other ballads on Astral Weeks, percussionist Warren Smith’s stringed overdubs are deliciously understated – providing a perpetual breeze to whatever climate Morrison and the band is crafting at the time.

“Cyprus Avenue,” the final composition of Side 1, is a three-chord blues composition, which has remained in the songwriter’s concert mix for five-plus decades. The musical and emotional centerpiece of Astral Weeks, “Cyprus Avenue” focuses on Morrison’s childhood in Belfast in lyrics that are both mystical and haunting. The tune is so luminously supported by bassist Richard Davis that Paul McCartney once called Lewis’s performance throughout the ballad, “immortal.” For me, I don’t know for sure about God or what happens to us all when we die. I wish I did. The big questions have always eluded me. But I do know that I could be dead a thousand years and the bass line from “Cypress Avenue” will still live inside some part of me. For that reason alone, I assume there is some form of an afterlife.

The fifth title, “The Way Young Lovers Do,” seems out of place with the rest of the compositions Morrison included in the album, a lounge singer’s paean, which Sinatra might well have recorded with bandleader Nelson Riddle. The subject of the song, an adolescent’s first kiss, however, fits well thematically with the rest of the numbers. As one friend once commented to me recently, Astral Weeks’ numbers are the kind that Holden Caulfield might have composed had he been a songwriter in the 1960s.

The most ambitious ballad on the release, “Madame George,” is a nine-minute excursion into the life of a Belfast boy who soaked up a wellspring of images growing up and who attempts to make sense of it all, including the people he observed along the way who marked his individual passage in time. In a record dominated by stream-of-consciousness lyrics, this composition is the most impressionistic and emotional of all eight musical numbers. Heartbreaking and evocative, “Madame George” remains the personal favorite for many devotees of Astral Weeks.

The rawness of the song is so over-the-top that it is almost voyeuristic. Coldplay’s Chris Martin admitted recently in a New York Times interview: “A few years ago, I was going through some personal shit, and I put Astral Weeks on, and it just tore right through me, especially ‘Madame George.’ I had to stop – turn it off. Of course, I’d heard it before, but this time it just hit me deep. I can’t remember ever having a reaction quite like that to an album. I haven’t listened to it since. I almost have a few times, but I felt oddly afraid of it.”

Raw, honest intensity can do that.

Luckily, Van places a decidedly more sanguine number, “Ballerina,” as the follow-up. In a way, this number is a love note to the possibilities as anything Morrison has ever recorded. He supposedly wrote it after watching his future spouse dance in rehearsal one afternoon in a secluded ballroom off of Boston’s Kenmore Square. “Not long afterward, we were a couple, we were residing in Cambridge, all was well, and I wrote ‘Moondance’ for her that first fall after I came back from recording Astral Weeks,” Morrison told Dave Marsh. “Ballerina” seems to embrace the notion first put forth by Bertrand Russell: “To fear love is to fear life, and those who fear life are already three parts dead.“

“Slim Slow Slider” completes the LP with an unanticipated shot across the bow. While the bookends of growing up for most have been framed by a combination of impulsivity and exploration, this might actually get you into trouble when you become an adult and have the undeniable guillotine of ongoing responsibilities hanging over you. In a poignant way, Van the Man says goodbye here to his youth even as he clings to it one last time. One is reminded of Dylan’s line, “I was so much older then; I’m younger than that now…” as “Slim Slow Slider” fades into nothingness to conclude the songwriter’s enduring tour de force.

When Astral Weeks was officially released in the last weeks of autumn in 1968, I paid it little heed as did the general public at the time. Unlike any other Morrison album, however, it has actually sold more and more copies each year – a word-of-mouth gemstone that never seemed to grow old with the passage of time. As my dear friend, The Reverend William Robertson, once stated to me, “You have to grow into Astral Weeks.“

By the late 1970s, I found myself working as an intern at a local Boston radio station for a spell. Superstition abounded, especially in such a kinetic business. One of the rituals for each disc jockey was to have his or her individual stack of records to be left on the shelf “in case the world ended.” It was nothing more than a personal preferred list, but each jockey would put his or her absolute favorite on the very top. After more than 50 years of literally thousands of exemplary musical releases framing my memory, Astral Weeks remains on top of my personal stack. I can’t imagine another release replacing it.

Like van Gogh’s sunflowers that are forever in bloom or the dancers who will eternally move like the wind in Alvin Ailey’s Revelations, the music of Astral Weeks will continually be an unyielding musical expression of the realization that the most wondrous of all ages – youth – is fleeting. I will listen to this record until my last days because it also contains the ultimate incongruity of life – that something so spontaneous – so spur of the moment – can concurrently touch the threshold of immortality.

I love Van. I l also love and admire good writing.

Kudos to the GCDS alums who inspired you to initiate this blog. There is a clear 2nd career or post career available to you. The next time you are similarly inspired, consider giving one of the major music journals a preview – for possible publication.

Terrific piece. Congratulations. Waiting for the next entry.

Doug lyons

LikeLike

Thank you so much, Doug. I really appreciate your comments. It is all very much a sidebar, but it does spur me on!

LikeLike