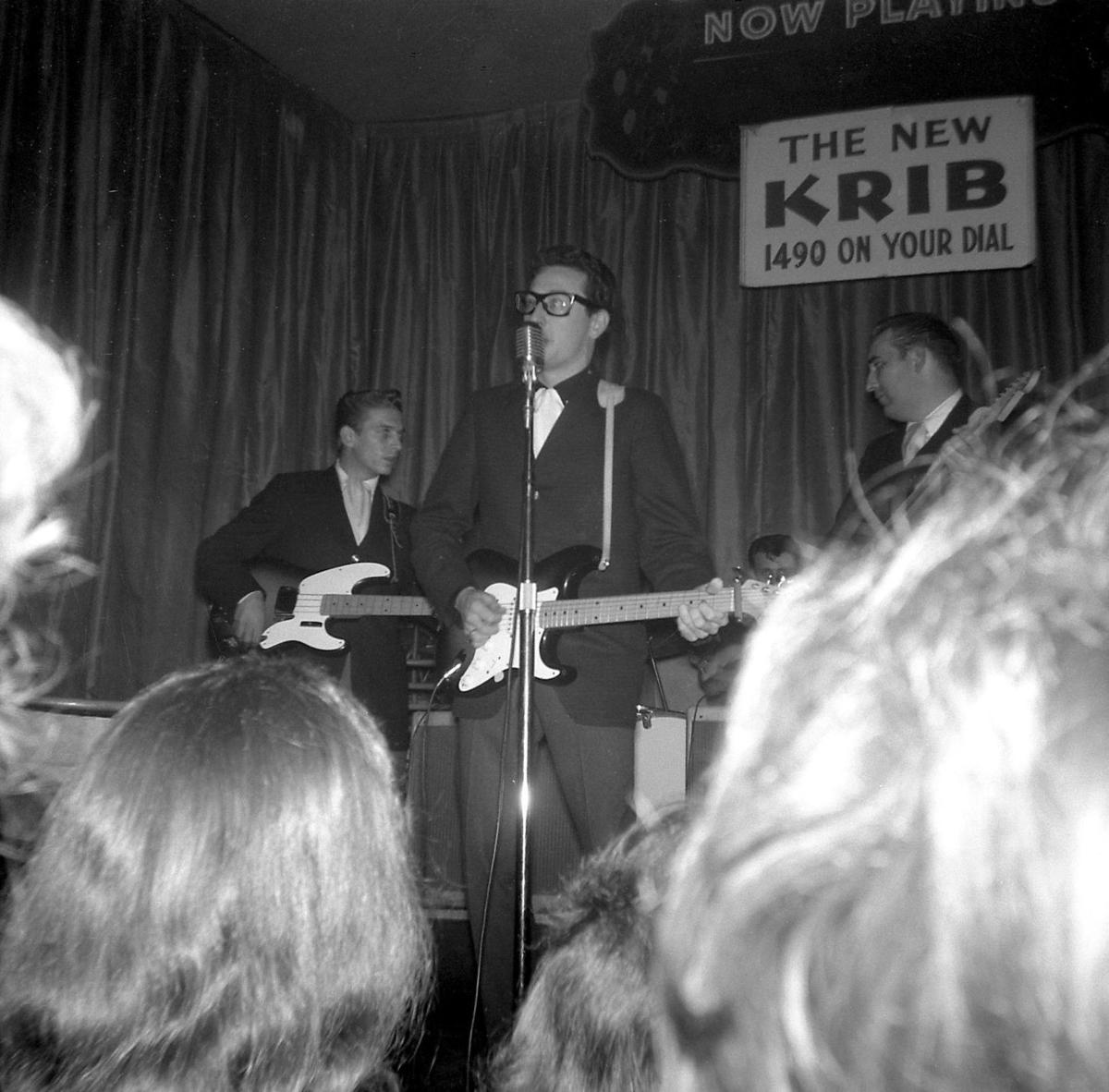

BUDDY HOLLY PERFORMING AT THE SURF BALLROOM – CLEAR LAKE, IOWA ON FEBRUARY 2, 1959 (Waylon Jennings and Tommy Allsup in the background).

On the evening of Monday, February 2, 1959, one of the most celebrated concerts in rock ‘n roll history concluded at exactly 11:07 CST at the Surf Ballroom in Clear Lake, Iowa as twenty-two-year-old Buddy Holly belted out an impassioned rendition of Chuck Berry’s “Brown-eyed Handsome Man” to an ecstatic audience of 1,200 teens who had paid $1.25 a ticket for the privilege of attending the three-hour-long extravaganza.

After hearing the Lubbock, Texas native’s cover version while on tour with him in during the spring of 1958, “Mr. Excitement,” Jackie Wilson, had declared that Buddy’s version of Chuck Berry’s 1956 recording was even better than the iconic original. Holly had subsequently recorded the number in Clovis New Mexico at Norman Petty’s studio, but it was waiting for the proper mixing and overdubs to be added once he returned from the winter tour.

“Buddy played with such a distinct intensity, particularly when he ended the show with ‘Brown-eyed Handsome Man,” recalled Holly’s bass player of his band that evening, fellow Texan Waylon Jennings. “You could hear his distinct Tex-Mex influence on his Fender Stratocaster, which bridged each verse of the tune. He was on fire – and the Clear Lake audience reacted accordingly. Buddy had a big grin on his face when he finished.”

Joining him on the stage for an encore of the number were his Winter Dance Party Tour mates – seventeen-year-old sensation Ritchie Valens, J. P. “The Big Bopper” Richardson, Dion and the Belmonts, and newcomer Frankie Sardo. “Thank you, Clear Lake!” Holly bellowed as he and his rock ‘n roll entourage left the stage to a final standing ovation.

Within minutes, Buddy was backstage meeting with Surf Ballroom Manager Carroll Anderson, who was in charge of securing a plane flight for the rock star and two other passengers from nearby Mason City Municipal Airport to Fargo, North Dakota, 360 miles to the northwest. According to the 19-day itinerary mapped out by the General Artists Corporation, Holly and his traveling Winter Dance Party Tour would next be playing in Moorhead, Minnesota – across the Red River from Fargo – the following evening. Anderson had already phoned Jerry Dwyer, who owned a local flying service. “We need a plane after the concert tonight if you can provide one,” Anderson requested. Dwyer replied that he had secured both a transport and a pilot, a local flyer, Roger Peterson, who was willing to fly in subzero temperatures and snow flurries after the concert.

11 days previously, the Winter Dance Party Tour had opened up in Milwaukee on Friday night, Jan. 23, 1959. It had then zigzagged from Wisconsin to Minnesota to Wisconsin to Minnesota to Iowa to Minnesota to Wisconsin and back to Iowa once again. It was evident that the group’s booking agent, the General Artists Corporation, paid little heed to either common sense or geography when the tour was organized in December 1958. As rock historian Bill Griggs recalled: “GAC just didn’t care. It was like they threw darts at a map. ‘The tour from hell’ – that’s what they named it at the time – and that’s what it turned out to be.”

From day one of the odyssey, the entire musical troupe had ventured together in a series of rentals. The reconditioned school buses used throughout the tour had proved to be utterly inadequate; four of them had already broken down as an extended cold spell hung over the region like a shroud. As was the norm in the early days of rock ‘n roll, the artists themselves had been responsible for loading and unloading equipment, often in lingering frigid temperatures. Additionally, the rickety buses they used were not equipped for the waist-deep snow and icy weather that awaited them at virtually every stop. “It was so bone-chilling on each of the vehicles we used that we had to wear all our clothes, coats and everything…I couldn’t believe how cold it was,” Waylon Jennings admitted in a Rolling Stone interview years later.

When the ensemble reached Clear Lake from Green Bay, Wisconsin, Richardson and Valens were already coming down with flu-like symptoms and Holly’s drummer for the tour, Carl Bunch, had to be hospitalized for frostbitten feet. On the last full day of his life, Holly had apprised Dion DiMucci that he had just decided to hire a plane to fly to the next point of entry so that he could sleep in a warm bed rather than ride on another all-night bus ride with insufficient heating. “My husband told me in a phone call from his Clear Lake dressing room that he also couldn’t wait to wear clean clothes for the following evening’s show in Minnesota. Buddy was determined to visit a laundromat in Fargo after he slept in a warm bed,” recalled Maria Elena Holly.

By the time Buddy ambled into Carroll Anderson’s car to drive the five miles to the Clear Lake Municipal Airport, he was, despite his youth, one of the most revered rock ‘n roll stars in the world. In a public career that lasted less than a thousand days, Buddy Holly had already chiseled out a breathtaking artistic legacy. First and foremost, he had been the first rock and roll star to compose, perform, and produce his own music. He had also introduced the concept of a three-guitar band, something unheard of previously in a genre that was still in its infancy. Holly’s use of double-tracking created an enriched sound in the studio, which revolutionized the way contemporary musicians recorded from then on. Buddy’s original folk ballad, “Well, All Right,” was the first rock and roll song to have an acoustic guitar play the lead on a major single.

In addition, his controversial recording session with the NBC Symphony Orchestra and über musical-director Dick Jacobs produced four string-laced ballads, including two top-ten hits in “It Doesn’t Matter Anymore” and “True Love Ways.” That session also proved to be another first as Buddy became the first rock and roller to ever record his music in stereo. Finally, Holly’s transformative infusion of country and western, Mexican, and rock influences between 1956-59 had created what would become known as “The Tex-Mex Sound.”

Just as notably, Buddy Holly proved to be a cultural trailblazer who had already cast a considerable light beyond the musical realm. In the summer of ‘57, he and his backup band, the Crickets, had become the first all-white rock group to play at Harlem’s fabled Apollo Theatre. The Father of Soul,” Sam Cooke, who had toured extensively with Holly that summer, was so impressed by his friend’s autonomy that Cooke ended up copying Holly’s business profile and became his own writer, producer, arranger, and record company executive with SAR Records until Sam’s own untimely death in December 1964.

A year later, when Buddy cut an original R&B tune entitled, “Reminiscing” and recorded it with revered rock-and-soul saxophonist, King Curtis, Holly broke another barrier. As Rolling Stone’s Dave Marsh pointed out, it turned out to be the first time that a Southern white rocker had recorded and subsequently released a song featuring a prominent African-American artist in a culture that was still largely segregated.

Because of the expanding popularity of his music, Buddy Holly ultimately made seven national TV appearances during his shortened career, including three live performances on the popular Ed Sullivan Show on CBS. His 1958 live appearances in both England and Australia broke new ground for the nascent musical form. Consequently, when he perished in the snows of Iowa 60 winters ago at the age of 22, Buddy Holly, already a major star, was just getting started.

For the 1960s generation of rock and roll fans, it was the Lubbock, Texas native ’s sustained musical influence that kept his memory alive, most notably with the most significant band in rock history, the Beatles. The Fab Four partially patterned their group after his backup group, the Crickets (“We were a three-guitar band, just like the Crickets. We even named ourselves after them. After all, we’re both insects who could sing,” John Lennon coyly remarked in his first American interview in New York in 1964). They also embraced the notion of forming their own sound as Holly had done. The Fab Four recorded their first song, Buddy’s “That’ll Be the Day,” in a small Liverpudlian studio on July 12, 1958. In the fall of 1964, at the peak of Beatlemania, the band ultimately enjoyed a top-five single with Holly’s 1957 hit record, “Words of Love.”

The week before his own tragic death, John Lennon told writer Jonathan Cott, “Buddy Holly was the first one that we were really aware of in England who could play and sing at the same time – not just strum, but actually play some great licks. We couldn’t get enough of him.” In The Beatles Anthology documentary series, Paul McCartney remarked: “All these years later, I still love Buddy’s vocal style…and his writing. One of the main things about the Beatles is that we started out writing our own material. People these days take it for granted that you do, but nobody used to then. John and I started to compose because of Buddy Holly. It was like, ‘Wow! He writes and is a musician’! In my mind, at least 40 songs from the Lennon-McCartney catalog are Buddy Holly-influenced.”

In 1982, when Buddy Holly’s musical catalog finally became available, Paul McCartney immediately bought the rights. For the past 39 years, he has stewarded the Holly goldmine with a mixture of both vigilance and veneration. “If Buddy couldn’t protect his music, I have made sure that I do,” Sir Paul said recently.

Waylon Jennings, who played bass for Holly during his last tour, recalled, “Buddy was the first person to have faith in my music. He encouraged me in my music and my writing. If anything I’ve ever done is remembered, part of it is because of him.” Dion DiMucci, who played with Holly throughout the ill-fated Winter Party Tour, called Holly…“ the best musician I ever had the pleasure of performing with – and I ended up playing with nearly all of the greats.”

In a New York Times interview, Mick Jagger recollected, “We all learned from Buddy Holly how to compose great songs. He was a beautiful writer.” Eric Clapton agreed: “Of all the music heroes of that era, Buddy was the most accessible.” Keith Richards called him…“ a revelation. You hear more of Buddy Holly in British rock songs than any other American artist.” Given his longstanding influence on the rockers who framed the British Invasion, it was not at all surprising that one of its leading bands, the Hollies, ultimately themselves after him.

On January 31, 1959, just four days before he died, Minnesotan Robert Zimmerman, soon-to-be-known as Bob Dylan, saw him play at the Duluth National Guard Armory during his senior year in high school. In his Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech in 2016, Dylan reminisced:

“If I was to go back to the dawning of it all, I guess I’d have to start with Buddy Holly. Buddy died when I was about eighteen and he was twenty-two. From the moment I first heard him, I felt akin. I felt related – like he was my older brother. I even thought I resembled him.”

“Buddy played the music that I loved – the music I grew up on – country western, rock ‘n’ roll, and rhythm and blues. Three separate strands of music that he intertwined and infused into one genre. One brand. And Buddy wrote songs – songs that had beautiful melodies and imaginative verses. And he sang great – sang in more than a few voices. He was the archetype. Everything I wasn’t and wanted to be. I saw him only but once, and that was a few days before he was gone. I had to travel a hundred miles to get to see him play, and I wasn’t disappointed.”

“He was powerful and electrifying and had a commanding presence. I was only six feet away. He was mesmerizing. I watched his face, his hands, the way he tapped his foot, his big black glasses, the eyes behind the glasses, the way he held his guitar, the way he stood, his neat suit. Everything about him. He looked older than twenty-two. Something about him seemed permanent, and he filled me with conviction. Then, out of the blue, the most uncanny thing happened. He looked me right straight dead in the eye, and he transmitted something to me. Something I didn’t know what. And it gave me the chills.”

The last half-hour of Buddy Holly’s life, of course, is now the stuff of legend. When he arrived at the Mason City Airport at 12:35 AM on February 3, 1959, Holly quickly met up with Carroll Anderson and paid him $36 for the one-way ticket to Fargo, North Dakota, where the Winter Dance Party Tour would entertain the next night. Anderson then introduced Buddy to Roger Peterson, 24, who was just two years older than Holly at the time. “We should arrive in Fargo sometime around 2:00 AM,” the Clear Lake pilot said confidently to his star passenger. Peterson then gave Holly a quick tour of the 1947 V-tailed Beechcraft 35 Bonanza, which would take them to North Dakota.

Earlier that evening, when Buddy had been informed that there would be extra seats on the single-engine plane, he eventually offered one of the seats to the Big Bopper, who was sick and needed rest. Holly then asked his old Texas friend, guitarist Tommy Allsup, to accompany him. Ritchie Valens, who was also feeling poorly, asked the Texan guitarist for his seat on the plane. The two agreed to toss a coin to decide who would go. Bob Hale, a disc jockey with Mason City’s KRIB-AM, was working the concert that night and flipped a half-dollar in the ballroom’s side-stage room shortly before the musicians departed for the airport.

Valens won the coin toss for the last seat on the flight.

When the trio of musicians and their pilot finally boarded the aircraft, the weather in Northern Iowa was overcast and freezing with occasional snow showers; temperatures were in the teens, and winds were gusting between 20 and 30 MPH from the southeast.

Jerry Dwyer witnessed the take-off at 12:55 AM from a platform outside the airport’s control tower. He was able to see the plane’s tail light for most of the flight, which started with an initial left turn onto a northwesterly heading and a climb to approximately 800 feet. Dwyer explained later to the FAA that he then observed the tail light gradually descending until it disappeared out of view.

The passengers were in the air for approximately four minutes before they crashed in a remote cornfield belonging to local farmer Albert Juhl. All four died instantly upon contact. The next morning, their frozen corpses were discovered after the plane failed to arrive safely in Minnesota. By noontime, it was the leading news story on virtually every radio and TV station across the nation. Eleven years later, singer-songwriter Don Maclean would immortalize the tragedy in his anthem, “American Pie,” calling Holly’s death, “The day the music died.”

Because I roomed with my oldest brother each summer at our grandfather’s cottage on Cape Cod, I began digging Buddy Holly’s music a year before he died. Through our shared record player, we habitually played such Holly 45 classics as “Early in the Morning,” “Peggy Sue,” “Rave On,” “That’ll Be the Day,” “Everyday,” and “Maybe Baby.” We also listened to his entire catalog of hits on WMEX Radio, Boston, which fervently played Holly’s music for years after his passing. When the Rolling Stones, the Who, Eric Clapton, the Grateful Dead, James Taylor, Linda Ronstadt, Bruce Springsteen, Elvis Costello, the Clash, Chris Isaak, The Foo Fighters, and Amy Winehouse all recorded Holly cover songs over the next six decades, Buddy’s music was periodically reenergized. In 1977, I befriended rock historian Bill Griggs and subsequently joined his Buddy Holly Memorial Society. Over the next 40-plus years, there would be two significant biographies, an acclaimed BBC/PBS documentary film, a longstanding Broadway show, and an Academy-nominated bio-picture all covering the short life and luminous career of the rock ‘n roll pioneer.

When the plane carrying him lifted off from the frigid runway at Mason City Airport on February 3, 1959, Buddy Holly was blissfully unaware of the danger that lay ahead, oblivious to everything but his reoccurring musical dreams. A minute later, as the Beechcraft 35 Bonanza flew over Clear Lake’s Surf Ballroom, Holly must have thought that he was approaching an incandescent musical career that would stretch on for years, even as a seedbed of adrenaline still surged through his body from the triumphant concert that had concluded an hour before in the picturesque Iowan town below.

Three minutes later, Holly was gone, cold-dead, forever in the past tense. Omnia enim et voluptas vana gloria.

Some 22,500 days later, though, his music lives on. In the end, “Not Fade Away” isn’t just the title of one of Buddy Holly’s more venerated hits.

It is his legacy.

14 BUDDY HOLLY-CONNECTED SONGS FOR YOU TO CHEW ON

“Not Fade Away,” 1957. Recorded in May, 1957, with his band, the Crickets, at producer Norman Petty’s legendary recording studio situated in Clovis, New Mexico, 100 miles northwest of Holly’s hometown of Lubbock, this, along with its A-side, “Oh, Boy,” were the logical follow-ups to the group’s first number-one single, “That’ll Be the Day.” As the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame pointed out when Holly was inducted in 1986, “Not Fade Away” was one of the first pop songs at the time to feature the “Bo Diddley” sound, a series of beats (da, da, da, da-da-da) popularized by Diddley, who used it on his first single in 1955. The signature beat originated in West Africa and was adopted by Diddley as his signature rhythm backup. Holly incorporated it with aplomb here and added some Tex-Mex chord progressions to create a new kind of sound. To add to the luster, Crickets drummer Jerry Allison played a cardboard box for percussion on this. (He’d heard Buddy Knox’ drummer do the same on his top-ten single, “Party Doll,” which had earlier been recorded at Petty’s Clovis studio). In 1964, the Rolling Stones had their first top ten hit with it. For years, Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band covered “Not Fade Away” as a natural encore selection. In so many ways, the original Holly number is an inspired hybrid of African-American, country-western, and Tex-Mex music.

“Everyday,” 1957. The flip side to “Peggy Sue,” “Everyday” features the celesta, a keyboard with a glockenspiel-like tone that Norman Petty kept in his New Mexico studio. On this recording, Vi Petty, the wife of the Crickets’ producer, did the honors. The unique percussion sound is actually drummer Jerry Allison keeping time by slapping his knees in unison for two minutes. For legal reasons, Holly changed his songwriting credit to Charles Hardin, his real first and middle names. This is Exhibit A in the Holly Catalog of Unexpected Musical Pleasures. Not surprisingly, the first four songs Holly recorded were flat-out rockers, but then Buddy threw this childlike ballad into the mix. Buddy said at the time, “I loved recording something that was just a little different.” At least two aspiring teenage rockers from Liverpool, England at the time took notice.

“Maybe Baby,” 1957. Recorded in September 1957 at Tinker Air Force Base in Oklahoma while the Crickets were on tour, Buddy composed the song on a General Artists Corporation tour bus, played it for Sam Cooke, who strongly urged him to record it as soon as possible. The reverberating downbeat of Buddy’s Fender Stratocaster is a revelation here as is the undercurrent of Joe B. Mauldin’s stand-up bass and Jerry Allison’s snare drum. As with nearly every Holly composition, the licks aren’t too hard to play, but they sound damn good anyway. Ultimately “Maybe Baby” is a quintessential Holly recording wrapped around an infectious melody and a tom-tom percussion change similar to what Dave Clark did years later with the DC Five. Like so many of his ballads, this is not only the template for rock ‘n roll songs in the sixties, but it’s a quintessential garage-band-tune as well.

“Reminiscing,” 1958. The big news here, of course, is that the late, great King Curtis plays the tenor sax in an inspired take that was so influential that it spurred a young Clarence Clemons of E Street Band fame to pick up the instrument. Curtis, who played on hundreds of songs – everything from the Coasters “Yakety Yak” to the Ben E. King’s “Stand By Me” to Aretha Franklin’s “Respect” to John Lennon’s “I Don’t Want to Be a Soldier” – befriended Holly while on tour with him in 1957. A year later, Buddy, who composed “Reminiscing” with Curtis in mind, invited him to record it with him at Norman Perry’s famed Clovis, New Mexico recording studio. The master of the 3-chord song, nevertheless, Holly let Curtis improvise here is a session that is profoundly historical – “Reminiscing” is the first time that a prominent white rock and roller recorded a number featuring a prominent African-American artist. While this was not a hit in the United States, it was in England. The Beatles ended up bringing it to Hamburg, where they played it regularly to German audiences in both 1960 and ‘61.

“Rave On,” 1958. Sonny West, a childhood friend of Buddy’s and fellow professional musician, composed this single and gave it to Holly’s producer, Norman Petty, who scheduled the Southwest rockabilly group, Jimmy Gilmer and the Fireballs to record it. (Gilmer and the Fireballs later had a hit with “Sugar Shack” with Norman Petty five years later). Buddy Holly knew how good the tune was and exclaimed, “No way, Norman, I’ve got to have this song!” His intuition paid off. In August 1958, “Rave On” was the number one single in both the US and Canada. In 2015, when Tom Petty played Buddy’s version on his Sirius radio show, he exclaimed, “Holly’s version of ‘Rave On’ is the epitome of rock and roll.” Everyone from the Rolling Stones to Prince has played it in concerts ever since. Bruce Springsteen has often remarked that “Rave On” is one of the greatest rock and roll songs of all time, and that he still psyches up for live performances by singing it backstage.

“Early in the Morning,” 1958. Buddy Holly not only wrote impeccable singles but he also left a treasure-trove of excellent covers as well. While “Early in the Morning” was a Bobby Darin composition, Buddy’s 1958 version outsold Darin’s and became a much-played single in the last summer of Holly’s life. The gospel-tinged call response throughout the number reminds us how “church music,” as Holly called it, resounded through Buddy’s music. In rock history, of course, this tune has a DNA that is hard to beat. While the Rolling Stones have always credited Muddy Waters’ “Rolling Stone” as the impetus to their name, Mick Jagger once said, “When Buddy Holly sang, ‘You know a rolling stone/don’t gather no moss,’ in ‘Early in the Morning,’ that kind of secured it for us.” Bob Dylan said the same thing after he composed, “Like a Rolling Stone.” Considering that Rolling Stone magazine ultimately based its name on the same Plymouth Rock, there are very few singles in rock history that have such a prodigious musical heritage.

“Well, All Right,” 1958. Recorded 61 years ago this spring, this acoustical foray into folk rock by one of the Founding Fathers of rock and rock is another example why Holly’s genius as both a composer and recording artist prevails all these years later. A single so influential that Bob Dylan said that he tried to model his first four albums on its “haunting simplicity,” the original Crickets back him up here, minus rhythm guitarist Nicky Sullivan. The flipside to “Heartbeat,” this single, like much of Holly’s work was more popular in the UK, where a young John Lennon tried to hash out the chords with the help of his mate, Paul McCartney. By 1959, the Quarrymen included “Well, All Right” in concerts at Pete Best mother’s venue, the Casbah Club. John sang the vocals while George Harrison ended up playing the acoustical lead. In 1979, when I interviewed the late Steve Goodman backstage at Passim’s, a prominent club in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the singer-songwriter-guitarist extraordinaire told me that he often played “Well, All Right” to remind him that “less is more – and that simplicity beats complexity most of the time.”

Brown Eyed Handsome Man, 1958. This classic Chuck Berry cover was the last number Buddy Holly ever performed at his legendary Clear Lake, Iowa concert at the Surf Ballroom on February 2, 1959. Less than two hours later, he would be dead in a plane crash. Regardless of that tragic reality, Buddy’s recording here is a pièce de résistance. Finally released in 1963, Holly’s version of “Brown Eyed Handsome Man” would go to number 3 on the British Top of the Pops survey that summer. You forget that Buddy Holly was both an exceptional and innovative guitarist – and then you’re instantly reminded when you here when you listen to his version of “Brown Eyed Handsome Man.” Chuck Berry famously claimed that Buddy Holly’s version of “Brown Eyed Handsome Man” remained his favorite cover of any of his songs. Tom Petty swore by Holly’s version and often played it on his much-beloved Sirius show, “Buried Treasures.”

“True Love Ways,” 1958. What a gem this first-generation recording is! It was rediscovered by Maria Elena Holly, Buddy’s widow nearly forty years after Buddy’s death. As you will hear, in the first ten seconds of the master, Holly can be heard preparing to sing. The audio starts with an unnamed female executive from Coral Records exclaiming, “Yeah, we’re rolling.” Pianist Ernie Hayes and tenor saxophone player Abraham Richman play some notes, and Buddy mutters, “Okay,” and clears his throat. Producer Dick Jacobs then yells, “Quiet, boys!” to everyone else in the room, and at the end of the talk-back, the producer says, “Pitch, Ernie,” to signal the piano player to give Holly his starting note, a B-flat. Buddy then flawlessly sings one of the most beautiful love songs recorded in the last 60 years. Recorded in stereo at the famed Pythian Temple in New York City at 135 West 70th Street on October 21, 1958, it was posthumously released as a single 14 months later. While the original sales in the US were somewhat disappointing, Holly’s stringed song hit number one on the UK charts, where he remained an icon. “True Love Ways” remains the ultimate teaser; the kind of ballad that Holly wrote in the last few months of his life that seemed to herald a different musical direction for the artist who loved to dabble. I can’t even imagine how many hits were unwritten because Buddy Holly died much too early.

“Love is Strange,” 1959. Originally recorded on Holly’s brand-new Ampex tape recorder in his Greenwich Village apartment 60 years ago on January 19, 1959, Buddy’s longtime producer, Norman Petty, later added the orchestration supporting his acoustic guitar after he died. Of course, “Love is Strange” was a crossover hit by American rhythm and blues duet Mickey & Sylvia, which was initially released in late November 1956 on the Groove record label. The tune was based on a guitar riff by the legendary Bo Diddley, which Holly duplicated here. Sadly, it was the last song that Buddy ever recorded, which is why Norman Petty reverently included the eerie organ background, performed by his musician wife, Vi. Holly’s mother, Ella, later said that it sounded as if her son was singing to her from heaven. If you haven’t ever heard this incredible version, you will notice that Buddy plays the song at 2/4 time, a radical departure from the original rockabilly tune that Diddley had originally written it in a few years previously. When Paul McCartney hosted a Sirius show on Holly’s memory a few years ago, he played “Love is Strange,” and remarked, “It’s almost as if Buddy knew something was going to happen.”

“Words of Love,” The Beatles, Live on the BBC, 1963. Even at the height of Beatlemania, the Fab Four play Holly reverently on this live studio recording, mirroring his chords and harmonizing Holly’s double-track recording almost to a T. The song was covered a year later by the band on their LP, Beatles for Sale. John Lennon and Paul McCartney harmonized on their version, while Ringo Starr played a packing case on this song as well as drums, to achieve a similar sound to Holly’s “Everyday.” Of course, the band had initially been named themselves the Beetles after the Crickets, but John Lennon’s artistic sense of wordplay altered it to – the Beatles. Here’s a live version of the Holly tune on the Beeb. As you will hear, they perform it with reverence.

“Rock Around With Ollie Vee,” From the Movie, The Buddy Holly Story, 1978. Yes, it’s Gary Busey playing Buddy Holly, but after all, he was nominated for an Academy Award for his performance – and deservedly so! What I always loved about this version was that Busey and his band successfully captured the energy and excitement of a star and his mates who dared to crossover from safe country & western to the much more daring and provocative realm of “bebop” as white people in Lubbock called rhythm and blues/rock back then. Talk about leaving your comfort zone! People forget that whites imitating blacks in the South back then was unheard of on so many levels. Like Elvis Presley, Buddy Holly found the various African-American sounds both evocative and enduring.

“Peggy Sue Got Married, Buddy Holly, 1959, and The Hollies, 1993. Graham Nash reunited with his old bandmates 24 years after he left the group in order to make this recording possible, a featured number of a project paying homage to Buddy Holly’s music. While Holly wrote and recorded the novelty song in his apartment in Greenwich Village a week prior to leaving on the Winter Party Dance Tour, the Hollies ended up dubbing their backup vocals and the supporting instrumentation, imagining, in Nash’s words, “what Buddy might have come up with in the final production had he lived.” By the way, the real Peggy Sue Gerron Rackham died on October 2, 2018, in Lubbock at the age of 78. Not long before she died, Peggy Sue, who dated and married Holly’s drummer, Jerry Allison in 1958, commented: “How wonderful that ‘Peggy Sue’ is still in the heart of every young man and in the spirit of every girl’s daydreams. Buddy Holly, my dear friend, the kid with black-rimmed glasses began this fairy tale romance with me when he recorded the song with my name. That fairy tale remains eternally young.”

“A Tribute to Buddy Holly,” Mike Berry and the Outlaws, 1961. When 22-year-old Buddy Holly perished in the crash of a private plane outside of Clear Lake, Iowa on February 3, 1959, more than 40 tribute songs to him were recorded over the years, including Don McLean’s “American Pie.” Two years after Holly died, Mike Berry, a renowned skiffle player from Northampton, England, wrote and recorded this poignant tribute, which remains the best tribute to Holly’s memory. According to Berry, the bridge refrain he sings… “was channeled right from Buddy. It almost sounds corny, but it came to me in a dream.” (Kudos to drummer Carl Betz for mirroring Jerry Allison by duplicating the “Peggy Sue” tat-at-tat-tat percussion). I agree with the late George Harrison who once told Beatles’ author Hunter Davies that… “‘A Tribute to Buddy Holly’ captures the essence of his music, his death, and his legacy better than anything I’ve ever heard.” Of course, Buddy Holly lives on in his music as this single poignantly implies.

As a lifelong fan of Buddy’s I truly appreciate your blog post and I have shared it on my Facebook and Twitter pages.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much, Bob! I really appreciate it!

LikeLike

Shaun, as a diehard rock ‘n roller, I have never read an author’s writings that hit home with me as yours do. Excellent. I, too, have shared this link with my FB friends hoping that they may appreciate the beginnings of the music that shaped my life.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much, Jim! This means a lot to me! It was really interesting to research and an honor to write. All the best, Shaun

LikeLike

In a further bid for immortality, Jerry Garcia and the Grateful Dead played their Holly tribute “Not Fade Away” thousands of times on tour and in the studio. It became one of their signature songs and further iterations of the Dead still play it live today. Well done, Shaun! Don McLean was right, but he was wrong!

LikeLike

As a non-Dead Head, I am thrilled that BH touched the music of the Dead. I am sure Garcia revered him as all of the rockers who came after him inevitably did. By the way, Springsteen’s live version of “Not Fade Away” is another one to die for.

LikeLike

Tommy Allsup was not a Texan, but a Cherokee native Indian descendant, from the Owasso suburb of Tulsa, Oklahoma.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This article is a wealth of information, not to mention meticulously written. Not only does it answer some burning questions I had about Buddy and his demise, it also answers the question as to why Buddy Holly has become such a huge part of my life. There was, quite simply, nobody else on the planet like him– and there never will be.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much, my friend. It was an absolute joy to write. Buddy’s music has been part of me since I heard “Peggy Sue” six decades ago. God bless.

LikeLike

Grew up on these guys. Thanks for the Memories

LikeLiked by 1 person

I appreciate it, Janet!

LikeLike

I am going on 77 January 28th. I do not remember when Buddy Holly music was not playing on my stereo, radio, computer or in my head. I have loved his music since I first heard it when I was 13 years old.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am going to be 66 on January 28! Wow!

LikeLike